|

If you've never heard of the animated Star Trek series, never knew that in the 1970's there was an animated spin off of that show with Captain Kirk and Mister Spock, you are not alone. It isn't any wonder even that many people who were around at the time have forgotten that there was such a show, especially considering what kind of turmoil the world was in in 1973. This is the story of the animated Star Trek - the forgotten chapter in Star Trek history. If you've never heard of the animated Star Trek series, never knew that in the 1970's there was an animated spin off of that show with Captain Kirk and Mister Spock, you are not alone. It isn't any wonder even that many people who were around at the time have forgotten that there was such a show, especially considering what kind of turmoil the world was in in 1973. This is the story of the animated Star Trek - the forgotten chapter in Star Trek history.

Filmation founders, (l to r) Norm Prescott,

Hal Sutherland, Lou Scheimer

Late in 1972 Norm Prescott and Lou Scheimer - top

executives at Filmation approached Gene Roddenberry

and Paramount about obtaining the rights to do an animated version of Star Trek.

Lou Scheimer had appreciated the original Star Trek series and thought that the

property could thrive as an animated series. Other production companies

also sought the rights to produce an animated Star Trek. Late in 1972 Norm Prescott and Lou Scheimer - top

executives at Filmation approached Gene Roddenberry

and Paramount about obtaining the rights to do an animated version of Star Trek.

Lou Scheimer had appreciated the original Star Trek series and thought that the

property could thrive as an animated series. Other production companies

also sought the rights to produce an animated Star Trek.

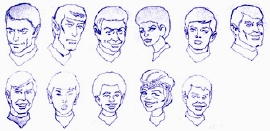

Unlike virtually all other Filmation series up to that time, and indeed most Saturday morning animated series, the animated

STAR TREK series would not be played for laughs, would not feature young characters, would not feature cute animal sidekicks and would not feature the characters singing in a rock-and-roll band. However, before meeting with Roddenberry, the Filmation staff did up some potential sketches of what some of the Enterprise crew might look like in animated form and some featured kids. Unlike virtually all other Filmation series up to that time, and indeed most Saturday morning animated series, the animated

STAR TREK series would not be played for laughs, would not feature young characters, would not feature cute animal sidekicks and would not feature the characters singing in a rock-and-roll band. However, before meeting with Roddenberry, the Filmation staff did up some potential sketches of what some of the Enterprise crew might look like in animated form and some featured kids.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Early Filmation concept sketches of several major characters.

|

These conceptual illustrations included a set that featured young counterparts to five members of the crew. Once these latter sketches were shown to Gene, however, the idea of kids on the show was immediately withdrawn and never revisited. These conceptual illustrations included a set that featured young counterparts to five members of the crew. Once these latter sketches were shown to Gene, however, the idea of kids on the show was immediately withdrawn and never revisited.

Early Filmation concept sketches

featuring new young characters.

|

Filmation promised to commit their best team of creative artists to the new project and pledged that the show would

adhere to the quality of story and characterization Filmation promised to commit their best team of creative artists to the new project and pledged that the show would

adhere to the quality of story and characterization  of the original and that the look

and feel of everything from the Enterprise interiors to the uniforms and props would be

authentic. Gene Roddenberry accepted Filmation's proposal to create an animated STAR TREK, but he insisted on maintaining creative control and insisted that D. C. Fontana (pictured left) serve as not only the new show's story editor, as she had done on the original series, but that she assume the duties of producer, although her credits list

her as Associate Producer. Gene was the show's executive consultant. of the original and that the look

and feel of everything from the Enterprise interiors to the uniforms and props would be

authentic. Gene Roddenberry accepted Filmation's proposal to create an animated STAR TREK, but he insisted on maintaining creative control and insisted that D. C. Fontana (pictured left) serve as not only the new show's story editor, as she had done on the original series, but that she assume the duties of producer, although her credits list

her as Associate Producer. Gene was the show's executive consultant.

The rights were granted to Filmation, and soon after, NBC bought the series. But although the show was presented as a serious program perfectly suitable for adult viewing

in prime time, the NBC executives considered it kiddie fare and relegated the show to

Saturday mornings and as a result it has become the forgotten Star Trek. When asked about the maturity level of the animated series during an interview for Show magazine in the early 1970's, Gene Roddenberry responded: "That was one of the reasons I wanted creative control. There are enough limitations just being on Saturday morning. We have to limit some of the violence we might have had on the evening shows. There will probably be no sex element to talk of either. But it will be Star Trek and not a stereotype kids cartoon show." The rights were granted to Filmation, and soon after, NBC bought the series. But although the show was presented as a serious program perfectly suitable for adult viewing

in prime time, the NBC executives considered it kiddie fare and relegated the show to

Saturday mornings and as a result it has become the forgotten Star Trek. When asked about the maturity level of the animated series during an interview for Show magazine in the early 1970's, Gene Roddenberry responded: "That was one of the reasons I wanted creative control. There are enough limitations just being on Saturday morning. We have to limit some of the violence we might have had on the evening shows. There will probably be no sex element to talk of either. But it will be Star Trek and not a stereotype kids cartoon show."

Filmation founders, (l to r) Lou Scheimer, Hal Sutherland, Norm Prescott

|

This new Star Trek show had a lot going for it. Many of

the original writers from the original series came back to write new episodes and sequels to their live-action episodes. These included "More Tribbles, More Troubles" by David Gerrold which was a sequel to his "The Trouble With Tribbles" episode. Chuck Menville and Len Janson wrote "Once Upon a Planet", a sequel to "Shore Leave" written by

Theodore Sturgeon. Stephan Kandel, author of two Harry Mudd episodes of the original series, returned to pen an animated Mudd tale, "Mudd's Passion". Even actor Walter Koenig, who had portrayed Ensign Pavel Chekov on the original series, wrote a script, "The Infinite Vulcan", which tied in to the original series episode "Space Seed."

D. C. Fontana, who had written some of the most

memorable episodes of the original Star Trek series, contributed a script which would be

recognized as one of the best Trek stories written, "Yesteryear". Fontana selected writers that would be able to maintain the quality and consistency of the Star Trek

concepts. Usually such animated projects employ animation writers, which are writers

versed in the peculiarities of the TV cartoon art form. But for Star Trek, fine sci-fi writers

provided the material. These scripts were then massaged by D. C. Fontana and the Filmation

staff to suit the animation technique. The availability of so many excellent writers was partially due to the fact that in early 1973 an eight-month writer's strike was underway. The strike prevented members of the Writers Guild of America (WGA) from writing for live action television programs. However, guild rules allowed authors to write one episode of an animated television series. The strike eventually ended in the summer of 1973. This new Star Trek show had a lot going for it. Many of

the original writers from the original series came back to write new episodes and sequels to their live-action episodes. These included "More Tribbles, More Troubles" by David Gerrold which was a sequel to his "The Trouble With Tribbles" episode. Chuck Menville and Len Janson wrote "Once Upon a Planet", a sequel to "Shore Leave" written by

Theodore Sturgeon. Stephan Kandel, author of two Harry Mudd episodes of the original series, returned to pen an animated Mudd tale, "Mudd's Passion". Even actor Walter Koenig, who had portrayed Ensign Pavel Chekov on the original series, wrote a script, "The Infinite Vulcan", which tied in to the original series episode "Space Seed."

D. C. Fontana, who had written some of the most

memorable episodes of the original Star Trek series, contributed a script which would be

recognized as one of the best Trek stories written, "Yesteryear". Fontana selected writers that would be able to maintain the quality and consistency of the Star Trek

concepts. Usually such animated projects employ animation writers, which are writers

versed in the peculiarities of the TV cartoon art form. But for Star Trek, fine sci-fi writers

provided the material. These scripts were then massaged by D. C. Fontana and the Filmation

staff to suit the animation technique. The availability of so many excellent writers was partially due to the fact that in early 1973 an eight-month writer's strike was underway. The strike prevented members of the Writers Guild of America (WGA) from writing for live action television programs. However, guild rules allowed authors to write one episode of an animated television series. The strike eventually ended in the summer of 1973.

To further embrace the expectations of the fans, the decision was made to make an extraordinary effort to reproduce the likenesses of Kirk, Spock, McCoy, Scotty, Sulu,

Uhura and Nurse Chapel. As many of the original actors as possible were brought onboard

to reprise their roles by providing the voices of their animated versions. At first,

Filmation planned on not having George Takei and Nichelle Nichols come back to do their

roles again. But when Leonard Nimoy learned of their exclusion he said that he would

"... not be a party to this if two of the minorities who contributed to making Star Trek

what it was when we were on television cannot be incorporated." It was due to Nimoy's stand that

Sulu and Uhura's characters made it into the animated series. So, DeForest Kelley was portraying McCoy once again. Kelley quipped, "Here we were a bunch of cartoon characters." But he welcomed the work since some of the twenty-two scripts were really very good - especially with D. C. Fontana producing and in the writing mix. Having been birthed in radio, for Kelley, reading dialogue for animation was child's play, and he really enjoyed himself. Eventually Fontana left the show after the first season because as she says, she "wanted to move on to something else, and not get stuck in animation. The business is funny. If you stay too long in one thing, people start to buttonhole you there and say, 'You can't do anything else,' regardless of all your other credits." To further embrace the expectations of the fans, the decision was made to make an extraordinary effort to reproduce the likenesses of Kirk, Spock, McCoy, Scotty, Sulu,

Uhura and Nurse Chapel. As many of the original actors as possible were brought onboard

to reprise their roles by providing the voices of their animated versions. At first,

Filmation planned on not having George Takei and Nichelle Nichols come back to do their

roles again. But when Leonard Nimoy learned of their exclusion he said that he would

"... not be a party to this if two of the minorities who contributed to making Star Trek

what it was when we were on television cannot be incorporated." It was due to Nimoy's stand that

Sulu and Uhura's characters made it into the animated series. So, DeForest Kelley was portraying McCoy once again. Kelley quipped, "Here we were a bunch of cartoon characters." But he welcomed the work since some of the twenty-two scripts were really very good - especially with D. C. Fontana producing and in the writing mix. Having been birthed in radio, for Kelley, reading dialogue for animation was child's play, and he really enjoyed himself. Eventually Fontana left the show after the first season because as she says, she "wanted to move on to something else, and not get stuck in animation. The business is funny. If you stay too long in one thing, people start to buttonhole you there and say, 'You can't do anything else,' regardless of all your other credits."

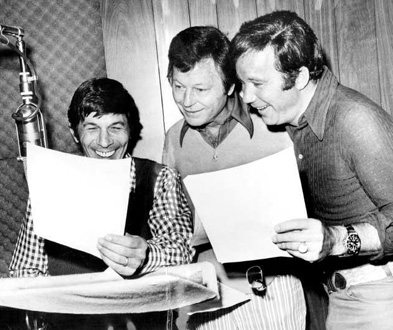

Voice actors, (l to r) Leonard Nimoy, DeForest Kelley, William Shatner

|

Unfortunately with that many star

voices, the budget simply didn't allow for Walter Koenig to return as Chekov. Due to an apparent

mis-communication between D. C. Fontana and Gene Roddenberry, Koenig was not officially informed that there

would be an animated series by either of them, but instead learned of it from a fan at a Star Trek

Convention. Koenig would later describe this situation as quite possibly the most embarrassing

Star Trek moment he ever had. James Doohan, who is

a speech expert of almost limitless talent, provided the voices of a large number of characters and

did double duty by doing the voice of Scotty and semi-regular character Lieutenant Arex.

On two episodes,

"Yesteryear" and "The Ambergris Element", Doohan provided

the voices of seven different characters. Majel Barrett similarly voiced numerous

female voices including Nurse Chapel, the semi-regular

Lieutenant M'Ress and of course the

Enterprise computer. George Takei and Nichelle Nichols also occasionally did some guest characters.

In an unprecedented way, several other guest star actors from the original series returned to do the

voices of their characters, such as Roger C. Carmel (Harry Mudd), Stanley Adams (Cyrano Jones),

and Mark Lenard (Sarek). So it was then, that in June 1973 almost the entire original cast of Star Trek

were reunited to once again do a Star Trek series! Unfortunately with that many star

voices, the budget simply didn't allow for Walter Koenig to return as Chekov. Due to an apparent

mis-communication between D. C. Fontana and Gene Roddenberry, Koenig was not officially informed that there

would be an animated series by either of them, but instead learned of it from a fan at a Star Trek

Convention. Koenig would later describe this situation as quite possibly the most embarrassing

Star Trek moment he ever had. James Doohan, who is

a speech expert of almost limitless talent, provided the voices of a large number of characters and

did double duty by doing the voice of Scotty and semi-regular character Lieutenant Arex.

On two episodes,

"Yesteryear" and "The Ambergris Element", Doohan provided

the voices of seven different characters. Majel Barrett similarly voiced numerous

female voices including Nurse Chapel, the semi-regular

Lieutenant M'Ress and of course the

Enterprise computer. George Takei and Nichelle Nichols also occasionally did some guest characters.

In an unprecedented way, several other guest star actors from the original series returned to do the

voices of their characters, such as Roger C. Carmel (Harry Mudd), Stanley Adams (Cyrano Jones),

and Mark Lenard (Sarek). So it was then, that in June 1973 almost the entire original cast of Star Trek

were reunited to once again do a Star Trek series!

Due to the demanding schedules of the voice actors during the show's production, it was sometimes

necessary for actors to record their dialogue alone away from the other actor's and then send tapes

of their performances to the studio where they could be mixed together with the other dialog to

form the show's soundtrack. There was even an occasion in which voice recordings had to be sent in

from actors all across the country in order to piece together a particular episode. Due to the demanding schedules of the voice actors during the show's production, it was sometimes

necessary for actors to record their dialogue alone away from the other actor's and then send tapes

of their performances to the studio where they could be mixed together with the other dialog to

form the show's soundtrack. There was even an occasion in which voice recordings had to be sent in

from actors all across the country in order to piece together a particular episode.

In June 1973, William Shatner, Leonard Nimoy, De Forest Kelley and all the rest of the cast voiced the first three episodes as an ensemble at the recording

studio located near the corner of Sherman Way, just outside of Hollywood. For subsequent episodes, actors would come in and record their lines at different times of the day -- with the actors meeting each other at the studio as one left and the other arrived.

The high standards of authenticity and quality drove the production cost to about $75,000 per

half-hour episode, making it the most expensive animated series of its time. Filmation took all of

this in stride and put forth an admirable effort. The show employed some 75 artists who produced 5,000 to 7,000 separate drawings per show, plus a host of other support personel. The primary problem facing the production company had to do with the ridiculous delivery date handed them by NBC executives. The network waited until

April or May 1973 to give the green light for the project which was to air in September of that

same year. The initial contract was for sixteen half-hour episodes to begin airing September 1973.

After that, six additional episodes were ordered for airing the following year, bringing the total

to twenty-two episodes. That meant that eight hours of animation had to be

created in just five months. At that time companies like Walt Disney produced two hours of final

animation in about two years. But of course in the 1970's animated television shows used what was

termed "limited" animation as opposed to "full" animation in which fewer different drawings were

used per second of screen time. In full animation upwards of 24 different drawings are used for

one second of screen time, whereas limited animation might have as few as 2 drawings per second at

its worst, but usually around 6 per second on average. Another cost cutting technique was to only

redraw the moving portions of a character. For instance a character's head and body may remain

stationary in a scene while only their eyes and lips move.

In June 1973, William Shatner, Leonard Nimoy, De Forest Kelley and all the rest of the cast voiced the first three episodes as an ensemble at the recording

studio located near the corner of Sherman Way, just outside of Hollywood. For subsequent episodes, actors would come in and record their lines at different times of the day -- with the actors meeting each other at the studio as one left and the other arrived.

The high standards of authenticity and quality drove the production cost to about $75,000 per

half-hour episode, making it the most expensive animated series of its time. Filmation took all of

this in stride and put forth an admirable effort. The show employed some 75 artists who produced 5,000 to 7,000 separate drawings per show, plus a host of other support personel. The primary problem facing the production company had to do with the ridiculous delivery date handed them by NBC executives. The network waited until

April or May 1973 to give the green light for the project which was to air in September of that

same year. The initial contract was for sixteen half-hour episodes to begin airing September 1973.

After that, six additional episodes were ordered for airing the following year, bringing the total

to twenty-two episodes. That meant that eight hours of animation had to be

created in just five months. At that time companies like Walt Disney produced two hours of final

animation in about two years. But of course in the 1970's animated television shows used what was

termed "limited" animation as opposed to "full" animation in which fewer different drawings were

used per second of screen time. In full animation upwards of 24 different drawings are used for

one second of screen time, whereas limited animation might have as few as 2 drawings per second at

its worst, but usually around 6 per second on average. Another cost cutting technique was to only

redraw the moving portions of a character. For instance a character's head and body may remain

stationary in a scene while only their eyes and lips move.

The animated Star Trek series had its faults mostly due to the limited range of action that could

be portrayed given the limited animation employed and the time pressures under which the series was

produced. However, one of the series greatest strengths was its ability to show alien life-forms,

cities, spaceships and spatial phenomenon that would have been cost prohibitive or downright impossible

to do in a live action series. In a way, the animated series was able to soar in the science-fiction

universe where the live-action series could only visit planetscapes that could be built on a small

soundstage or found on the Paramount backlot, and could only interact with aliens that could be

created by applying inexpensive amounts of make-up to human actors. The animated Star Trek series had its faults mostly due to the limited range of action that could

be portrayed given the limited animation employed and the time pressures under which the series was

produced. However, one of the series greatest strengths was its ability to show alien life-forms,

cities, spaceships and spatial phenomenon that would have been cost prohibitive or downright impossible

to do in a live action series. In a way, the animated series was able to soar in the science-fiction

universe where the live-action series could only visit planetscapes that could be built on a small

soundstage or found on the Paramount backlot, and could only interact with aliens that could be

created by applying inexpensive amounts of make-up to human actors.

The animated Star Trek series was a true bridge

between the original live-action series and the later movies and series in that the animated series

contained several Star Trek firsts. These include the first appearance of a holodeck in

"The Practical Joker", the first native American crewmember in

"How Sharper Than a Serpent's Tooth", and the mentioning of Captain Kirk's

middle name in "Bem". In the original series the bridge of the

U.S.S. Enterprise had only one exit. In 1973, the animated series featured a bridge with two

exits. Six years later, Star Trek: The Motion Picture, showed the bridge of the Enterprise with

two exits. Of importance to the Star Trek universe, the animated series not only mentioned, but showed

Commodore Robert April, the first commander of the Constitution-class Enterprise. The animated Star Trek series was a true bridge

between the original live-action series and the later movies and series in that the animated series

contained several Star Trek firsts. These include the first appearance of a holodeck in

"The Practical Joker", the first native American crewmember in

"How Sharper Than a Serpent's Tooth", and the mentioning of Captain Kirk's

middle name in "Bem". In the original series the bridge of the

U.S.S. Enterprise had only one exit. In 1973, the animated series featured a bridge with two

exits. Six years later, Star Trek: The Motion Picture, showed the bridge of the Enterprise with

two exits. Of importance to the Star Trek universe, the animated series not only mentioned, but showed

Commodore Robert April, the first commander of the Constitution-class Enterprise.

The series was even awarded an Emmy Award for the Best Children's Series for the 1974-75 season. It was canceled after 22 episodes, even though it was a critical success. Cecil Smith had written in the September 10th, 1973 Los Angeles Times: The series was even awarded an Emmy Award for the Best Children's Series for the 1974-75 season. It was canceled after 22 episodes, even though it was a critical success. Cecil Smith had written in the September 10th, 1973 Los Angeles Times:

|

If you've never heard of the animated Star Trek series, never knew that in the 1970's there was an animated spin off of that show with Captain Kirk and Mister Spock, you are not alone. It isn't any wonder even that many people who were around at the time have forgotten that there was such a show, especially considering what kind of turmoil the world was in in 1973. This is the story of the animated Star Trek - the forgotten chapter in Star Trek history.

If you've never heard of the animated Star Trek series, never knew that in the 1970's there was an animated spin off of that show with Captain Kirk and Mister Spock, you are not alone. It isn't any wonder even that many people who were around at the time have forgotten that there was such a show, especially considering what kind of turmoil the world was in in 1973. This is the story of the animated Star Trek - the forgotten chapter in Star Trek history. "NBC's new animated Star Trek is as out of place in the Saturday morning kiddie ghetto as a

Mercedes in a soapbox derby.

"NBC's new animated Star Trek is as out of place in the Saturday morning kiddie ghetto as a

Mercedes in a soapbox derby.  Don't be put off by the fact it's now a cartoon... It is fascinating

fare, written, produced and executed with all the imaginative skill, the intellectual flare and

the literary level that made Gene Roddenberry's famous old science fiction epic the most avidly

followed program in TV history, particularly in high I.Q. circles.

Don't be put off by the fact it's now a cartoon... It is fascinating

fare, written, produced and executed with all the imaginative skill, the intellectual flare and

the literary level that made Gene Roddenberry's famous old science fiction epic the most avidly

followed program in TV history, particularly in high I.Q. circles. NBC might do well to consider moving it into prime time at mid-series..."

NBC might do well to consider moving it into prime time at mid-series..."

In its initial network run, the show was not seen by most adults due to its early Saturday

morning time slot. In syndication, however, more and more people watched it and they came to

realize that even though it was a cartoon, it added another 22 stories to the Star Trek Universe - a great many of which were superbly crafted tales. In regards to the animated series' demise, Gene Roddenberry would write, "I think one can always wish something was done better, but within the limits of how animation is done in the market today - the speed it's done, the dollars they're able to put into it, and so on - it was a fairly good job. I think the best proof of that is the Emmy it won. Star Trek has a spectacular record of getting awards and special attention either while or after it's been canceled."

In its initial network run, the show was not seen by most adults due to its early Saturday

morning time slot. In syndication, however, more and more people watched it and they came to

realize that even though it was a cartoon, it added another 22 stories to the Star Trek Universe - a great many of which were superbly crafted tales. In regards to the animated series' demise, Gene Roddenberry would write, "I think one can always wish something was done better, but within the limits of how animation is done in the market today - the speed it's done, the dollars they're able to put into it, and so on - it was a fairly good job. I think the best proof of that is the Emmy it won. Star Trek has a spectacular record of getting awards and special attention either while or after it's been canceled."